The Command That Doesn't Exist: Why cd is a Builtin

If you have used a Unix-based OS like Linux or macOS, or if you’ve learned a little systems programming, you’ve likely heard the phrase: “everything is a file.” This principle implies that almost everything in the system (devices, processes, network sockets, etc.) can be represented as a file descriptor.

If you look into directories like /bin or /usr/bin, you’ll see that the commands you use daily are just executable files sitting in those folders. You could even rewrite them from scratch if you wanted to. For example, you could write your own implementation of ls in C, compile it, and never touch the system ls again.

But no matter how skilled a programmer you are, there is one command you cannot write yourself. You cannot create your own external executable for cd.

Let’s try to write our own cd (change directory) tool in C, and then look at why it is impossible to make it work.

Here is a very simple C program that attempts to change directories:

int

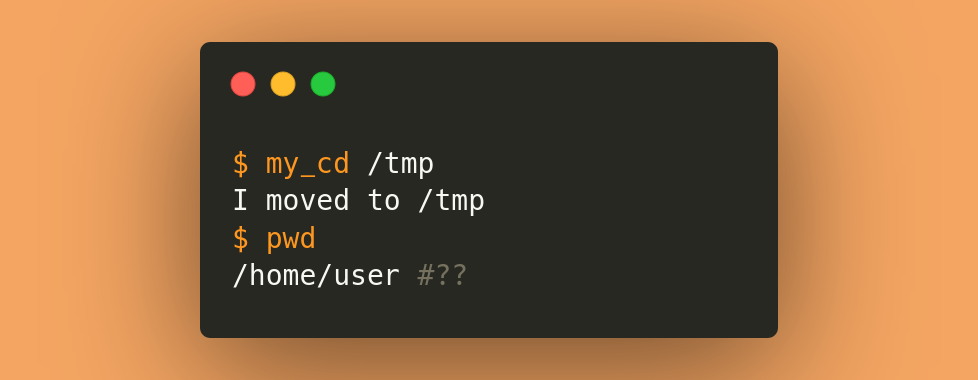

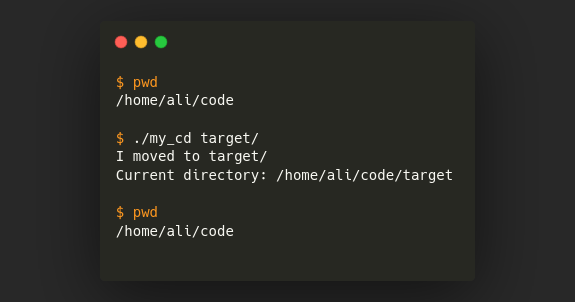

I compiled this code as a program named my_cd and tried to use it to enter a folder named target. Here is what happened:

As you can see, my_cd successfully claimed “I moved to target.” However, when I ran pwd (print working directory) command immediately after, I realized I hadn’t moved at all.

So, why did this happen?

The code didn’t crash. The chdir function returned success. Yet, we are still in the same place. To understand this, we need to look at how processes work under the hood.

Environments and Child Processes

Step 1: Bash is waiting

Every running program in Linux is a process. Every process has its own environment, which stores internal state like the current location.

You can run the

envcommand to see your current environment variables. ThePWDvariable holds your Present Working Directory.

[ Process: BASH (PID 101) ]

| Status: Running

| CWD: /home/ali/code

Step 2: User runs my_cd target

When a process starts another process (like running a command in the terminal), the OS spawns a new Child Process. This child gets a copy of the parent’s environment. The child then runs independently of the parent.

[ Process: BASH (PID 101) ] [ Process: MY_CD (PID 102) ]

| Status: Waiting -> | Status: Running

| CWD: /home/ali/code | CWD: /home/ali/code

Step 3: my_cd calls chdir()

Changes made inside the child process (like changing the working directory) only affect that specific child’s environment. The parent’s environment remains untouched.

[ Process: BASH (PID 101) ] [ Process: MY_CD (PID 102) ]

| Status: Waiting | Status: Running

| CWD: /home/ali/code | CWD: /home/ali/code/target <-- CHANGED!

Step 4: my_cd finishes and control returns to Parent

[ Process: BASH (PID 101) ]

| Status: Running

| CWD: /home/ali/code <-- STILL HERE

This is exactly why cd cannot be an independent program. So, how does the real cd command work?

Builtin Commands

Builtin commands are functions defined directly inside the shell (Bash, Zsh, Fish, etc.) source code. When you run them, the shell does not look into your PATH for an executable file. Instead, it executes its own internal function. This allows it to modify its own internal state.

If we want to change the state of the current Bash process, Bash itself has to perform the action. That is why cd is implemented as a shell builtin.

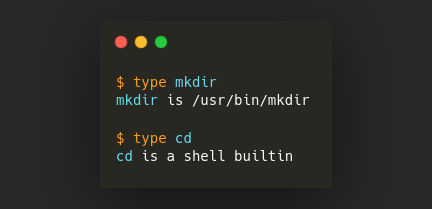

We can verify this using the type command:

Actually, there is a file named

cdon your computer, usually at/usr/bin/cd. But it is not a real program; it is a tiny shell script. If you look at the content, you’ll see this:This script exists purely for POSIX compliance and edge cases where automation tools (using

findorexec) expect a file to exist on the disk. It doesn’t actually work for navigation. If you try running/usr/bin/cd target, it will fail just likemy_cddid. It launches a child shell, moves the child, and then the child dies.

Mandatory Builtins

cd isn’t the only command that cannot exist independently. There are several other commands that must run inside the shell’s process. Here are a few examples:

exit

The simplest example of why builtins are necessary is exit. If we tried to make exit an external program:

int

This program’s only purpose is to close. But since it runs as a child, it would only close itself. It would not—and could not—close your terminal window.

Its only purpose is to terminate the process. If you ran this from your shell, it would execute as a child process. It would successfully terminate itself, but it could not possibly terminate its parent, the shell. Therefore, exit must be a builtin so it can execute within the current shell’s process and end your shell session.

source

You have likely used the source ~/.bashrc command to apply changes to your currently running terminal after editing your Bash configuration. In reality, the .bashrc file consists of nothing but ordinary bash commands; we can essentially call it a bash script. However, while we typically run other bash scripts using bash script.sh or (if executable) ./script.sh, the reason we execute the .bashrc script using source is—just like with cd—because we want to execute this script inside the existing process.

We could actually run the .bashrc script as bash ~/.bashrc, but in that case, we would encounter the exact same problem we faced with the my_cd program. A new bash process would start, and the script would run there—meaning the changes we want would be applied only to that new bash process. When the command finishes, the child process closes, and absolutely no changes would occur in our current bash.

So the source command is a builtin that tells the current shell to read the file and execute the commands right here, right now, without any child process.

And actually that is how you use virtual environments in Python. When you run source venv/bin/activate, it modifies your current shell environment to use the virtual environment’s Python interpreter.

Performance Builtins

The commands above have to be builtins to function. However, there is another category: commands that don’t need to be builtins, but are builtins anyway for speed.

echo

echo is very simple. We use it constantly in scripts, often inside loops. If echo were an external program, the OS would have to create a new process, allocate memory, load the binary, run it and destroy the process every single time you wanted to print a line of text. This would be a massive waste of resources.

If a small script you wrote had 10 echo commands, that one script would spawn 10 child processes just to print text to the terminal.

By making echo a builtin, the shell avoids all that overhead.

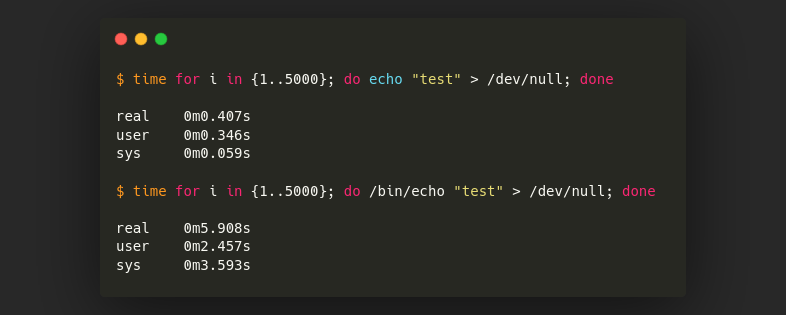

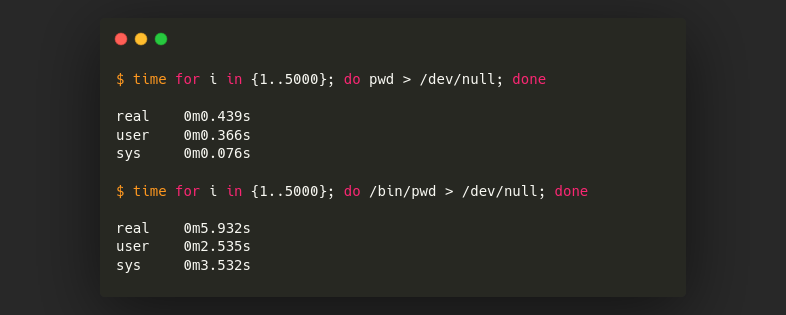

Interestingly, unlike cd, there is a real executable binary for echo (usually /bin/echo). But when you type echo, Bash ignores the binary and uses its internal function. We can see the performance gap by comparing the two:

pwd

Like echo, pwd doesn’t strictly need to be a builtin. The child process inherits the environment, so an external pwd program could easily read the PWD variable and print it.

However, just like echo, we use it often enough that the overhead of forking a process isn’t worth it. Comparing the builtin vs. the binary shows the same performance difference:

Summary

It is a misconception to think that every command you type in the terminal is a file sitting on the disk. The operating system maintains a delicate balance between process isolation and performance optimization.

Commands like cd are part of the shell because the rules of isolation leave them no choice. Commands like echo are part of the shell because we want them to be fast.

So, if you really want to write your own cd, you have to write the whole shell.

Next time you are curious, use the type command to see what you are actually running.